The Sinterklaas tradition in its current configuration is an invocation of, and invitation to, racialized pleasure and I want to consider seriously the dynamic between racism and pleasure, or the concept “racism as pleasure,” embedded in the Sinterklaas tradition. Racism is reproduced over time through pleasure, through embodiment, and through, what Robin Bernstein would term, “dances with things.” People take pleasure in dressing up, and acting, as Zwarte Piet. As such, pleasure plays an important role in the psychological investment that gives Zwarte Piet its cultural currency. Moreover, one of the main arguments used in defence of Zwarte Piet is that Sinterklaas is a “fun” and joyous occasion for children and by getting rid of the figure we are denying children a source of pleasure.

Pleasure and racism, as well as the pain and (ongoing) trauma of slavery and colonialism, are all intertwined in the Sinterklaas tradition, which essentially (re)packages (the trauma of) “slavery as racially innocent fun.” The historical memory that the figure of the black contains gets obscured through a ritualized “obliviousness to history and to race.” Anthony Paul Farley argues in The Black Body as Fetish Object that race is “a form of pleasure in one’s body which is achieved through humiliation of the Other and, then, as the last step, through a denial of the entire process.” Zwarte Piet, it is argued, is black because of soot. He is not a slave, but an indispensable manager. The Sinterklaas tradition isn’t racist; it’s for children. Blackface imagery, as Robin Bernstein notes, “thrives under the light cover of children’s culture and its penumbra of racial innocence.” And, the pleasure of innocence is enhanced by the pleasure derived from watching “black people,” these spectres of the White imagination, make a fool of themselves. Racial domination as pleasure in the Sinterklaas tradition is produced through a ritualized denial of race and an intimate choreography between Sinterklaas and Zwarte Piet, in which the figure of Zwarte Piet acts as a sign for subjugation, punishment, and pleasure. Anthony Paul Farley contends that “[T]he black body is the result of [this] convergence of power, knowledge, and pleasure.”

There has been an inordinate amount of focus in the Netherlands on the pain that racism causes, however, there’s very little attention paid to the possibility that enacting racism might be experienced as pleasure. George Lipsitz argues that racism doesn’t manifest itself “exclusively through hostility and exclusion.” Pleasure, joy and triumphant emotions, as well as hate and hostility, drive the processes of societal racism. “Personal feelings of antipathy and prejudice are not,” as Steve Martinot contends, “the core of racism; they arise in defense of an identity and a sociality of dominance.” Moreover, a sociality of violence or power is not, as Tim Cresswell states, “simply about control and regulation through denial, but about the production of pleasure itself,” which allows people to accept violence as sociality.

However, pleasures may be anticipated, experienced, and remembered in starkly different ways. It is by finding pleasure in and through rehearsed rituals and established objects that we become part of the community. Sara Ahmed tells us that when objects, like Zwarte Piet, give us pleasure, “we are aligned; we are facing the right way. We become alienated—out of line with an affective community—when we do not experience pleasure from proximity to objects that are attributed as being good.” Whiteness is (re)produced from within society through choices of association and identity—not through individual moral errors. Having said that, these choices do say something about the dominant public morality.

Despite the various appeals to pleasure, and childhood sentiment, the affective, psychological, and material investments of White Autochtoon Dutch bodies in the status-quo are hardly examined. White folks have, as George Lipsitz states, an “investment in images that whites themselves have created about people of color.”

Contrary to the dominant understanding, Zwarte Piet is presented in Dutch folklore as being a black man. In the story Moriaantje Zwart Als Roet (Little Moor Black as Soot) Zwarte Piet falls and breaks his leg. Sinterklaas becomes desperate, because he can’t do without his servant, who knows his way over the rooftops. Then Zwarte Piet provides a solution. He writes a letter to his cousin (or nephew) Moriaantje black as soot, who lives far away in Africa and asks him to take his place.

The Zwarte Pieten who accompanied Sinterklaas during the 1934 Amsterdam “Sinterklaasintocht” were Surinamese sailors whose ship happened to be lying in the port.

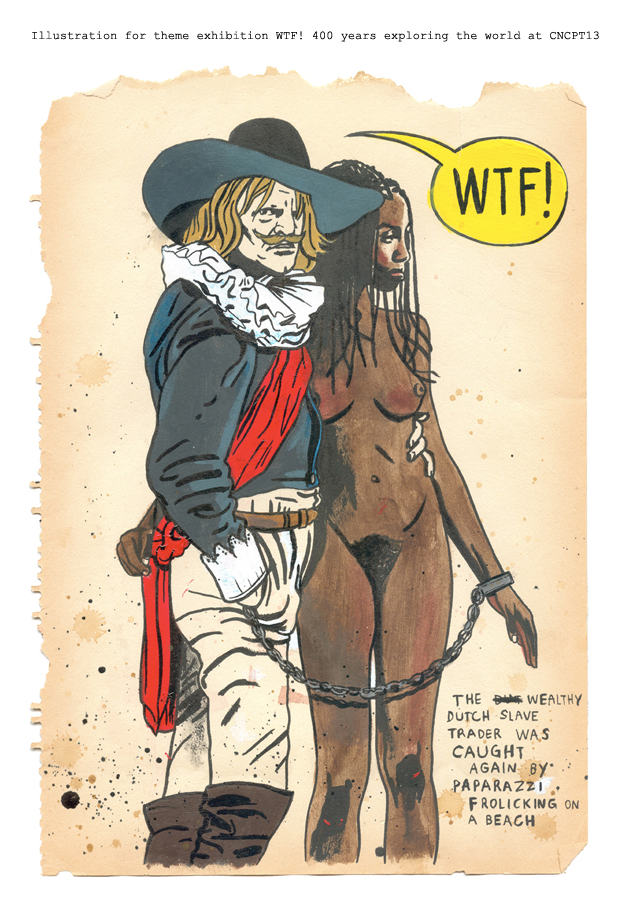

For Susan Willis, “blackface is a metaphor for the commodity,” a metaphor for enslaved Africans who were treated as though they were commodities or “products” for consumption. Blackness and black bodies are relegated (if not confined) to the realm of representation and performance. Through “the technology of blackface,” the black body is made subject to control, and turned into a source of pleasure and profit and it is through the means of an economy of desire, or pleasure that blackness gains currency. Saidiya Hartman remarks, that “the formal features of this economy of pleasure and the politics of enjoyment” should be “considered in regard to the literal and figurative occupation and possession of the body.” In the economy of desire, the black body, then, is never divorced from possession, profit, and pleasure. Thus, the value of the black body, as Penelope Ingram states, “resides not in [his] self-consciousness, [his] subjecthood, but precisely in [his] labor and the price exacted from such labor, [his] objecthood.”

The economy of desire is an apparatus of knowledge that fixes certain groups of people into a certain place, and attributes differential value to different bodies. In Alleen Maar Nette Mensen the main character says about Black people “Hoe zwarter, hoe dichter bij de natuur”—the blacker, the closer to nature. In the economy of desire “dark skinned” represents, for instance, an “animalistic” nature. The black body’s sexual, bestial excess is continuously being re-inscribed in popular culture and it is through this process of constant re-inscription that “dehumanization achieves ideological normality.” Advertising and marketing, as “unintentional” structures of anti-blackness, (re)produce racist ideology and affect in society, and offer tiny but unrestricted windows into the non-Black imaginary.

In our visual culture White people are seduced to enjoy moor heads, Negro’s/nigger’s kisses (or negress’ tits), and indulge in Chocodreams (see also South Park’s Chef’s Chocolate Salty Balls). This process of gendered and racialized dehumanization breaks down the black body and turns her bodily fragments into objects of value/consumption for White desire. Negro’s/nigger’s kisses, negress’ tits, moor heads conjure up “the dismemberment of the black body for souvenirs,” which often followed the lynching event. Neger has always been only part of the problem with negerzoen or negerinnentet. Negerzoen stresses the edibility of the black body and puts forward that we don’t even own our expressions of affection—even our bodily gestures of intimacy can be commodified, sold, and consumed.

Moreover, edibility of Negress’ tit “gestures toward the beliefs that motivated its theft,” and “anchors itself in its ability to bring the sensation of the other—an other person or another place—into one’s own body or conception of self.” The White desire to consume the black body suggests not only a desire to obliterate it, but also a desire to diagnose the black body only in terms of her capacity to regenerate Whiteness.

Both Negress’ tit and Negerzoen are rooted in the structures of White authority associated with racial intimacy during slavery. During slavery White men and women exercised control over and could, thus, (re)define and (re)structure the most intimate relations and activities of enslaved Africans. The implementation of slave laws meant, for instance, that “white men and women could exercise intimate power through punishment, torture and control of all a slave’s physical needs.” The captive and colonized body was effectively severed from “its motive will, its active desire.”

Intimacy and sex in the colonial project were, as Ann L. Stoler confirms, “always about racial power” and both sex and desire “were contingent upon a particular representation of non-white women’s bodies.” Crispin Sartwell intimates that, “the dirtiest secret of white racism is its eroticization of dominance.” What mattered then, and arguably still matters now, is accessibility to black bodies.

Annemarie Oster, a White Dutch actor, wrote in one of her columns, in which she bemoans her aging body and reminisces about the days she used to have gangbangs with 20 “negers,”

“Inmiddels zijn er vele jaren verstreken en zien zelfs negers mij niet meer staan.”

[Many years have now since passed, and not even Negroes/niggers notice me anymore.]

In the end, all that matters is the (re)generative pleasure that the black body gives. The black body continues to signify “property plus.” White desire of the black body is centred on the needs of White folks; it is a relationship between a human and a thing. I desire this thing because of how it stimulates me. Essentially, that kind of psychical relationship is nothing like the psychical relationship that White men have with other White men. Sinterklaas exercises control over unruly blackness; Zwarte Piet is positioned as the bringer of gifts or punishment. The black body is positioned, at once, as dangerous and domesticated, both in the sense of an object converted to domestic uses as well as accustomed to household life and affairs, so as to induce a sense of comfort and titillating pleasure. Jan Nederveen Pieterse argued that Zwarte Piet is an erotic figure; Pieterse notes that “sweeping the chimney,” a task supposedly performed by Zwarte Piet, is a sexual metaphor. In UN/SUB Sherman Fleming teases out the latent erotics of Sinterklaas.

[vimeo http://vimeo.com/39025231]UN/SUB is “a meditation on how the Dutch in their inability to fully address [their own] racial issues (the presence of a burgeoning African and Moluccan population) literally confectionalize and consume the body of color through the Sinterklaas (Santa Claus) ritual of eating a gingerbread doll, the tai-tai pop.” The thingification of Black bodies, the infantile dependence on and attachment to blackface, and the references to iconic colonial commodities expose the Sinterklaas tradition as “a realm neither of populist desire nor of commercially imposed distraction, but a stage on which appropriated goods and manufactured daydreams are transformed into culture.”

Frantz Fanon argued that racism is a projection of the desire of the White man onto the Black man, where “the white man behaves ‘as if’ the Negro really had them.” Blackface, as a sign of anonymity and illegibility, is centred on a desire of White Autochtoon Dutch people to inhabit the bodies of black people—to impersonate us. Blackface allows White folks to leave the body temporarily behind. It is a form of racial and political domination.

Racism, as Anthony Paul Farley notes, “is a pleasure which is satisfied through the production, circulation, and consumption of images of the not-white.”

The grammar of these “images of the not-white,” of darkie iconography, reproduces the black body both visually and textually and these discourses script the black body as socially deviant, infantile, hypersexual, violent, buffoonish, selfish, servile and out of control. And it is this mix of danger and pleasure that makes the promise that the black body holds so alluring; this “violence-induced fungibility of Blackness” underscores the thingness and sensuality of the black(ened) body, and allows for the appropriation of Blackness “by White psyches as ‘property of enjoyment.’” The reduction of the black body to a thing of pleasure perpetuates the brutal violation of African bodies by White male supremacy from the beginning of the transatlantic slave trade.

Hortense Spillers details in her essay Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book the deep and diasporic implications of the thingification, i.e. the capture and commodification, of Africans, and their delivery to the West. Spillers suggests that the sexualities of enslaved Africans provided, as a result of the thingification of enslaved Africans, “a physical and biological expression of ‘otherness,’” and “as a category of ‘otherness,’ the captive body translates into a potential for pornotroping.” Pornotroping violently reduces the captive body to flesh—to a sensuous thing embodying sheer powerlessness—and then displays this flesh to incorporate the viewing subject/body. Hortense Spillers illustrates the difference between the “captive” and “liberated” body by making a distinction between body and flesh, whereby the latter is without gender, and, thus, denotes an utter lack of “social conceptualization” in addition to a particular vulnerability to symbolic inscriptions. The visual language of darkie, or “slave iconography,” as Michael Chaney argues, “equates black people to a state of fleshliness,” and flesh is without gender.

Under the strictures of slavery and colonialism both the female and male body became “a territory of cultural and political maneuver, not at all gender-related, gender-specific.” Gender relations came to “mean nothing under a legal system that sanctions the treatment of humans as property.” The undoing and reconfiguration of black gender relations is a central aspect of slavery as social death. Sharon Holland notes in Raising the Dead: Readings of Death and (Black) Subjectivity that,

“If we as critics are going to work with the legacy of slavery, then we must engage in the ‘‘retrieval of mutilated female bodies’’. The grossness (as quality and quantity) of the flesh—‘‘matter’’ torn away from the body by mutilation and the society’s ‘‘cultural vestibulary’’—is a zone where the marking of culture appears on the flesh and the making of culture happens because of this constant abuse. Disallowed access to all culture but representative of it, black bodies become the literal containers of the power of state ideology and simultaneously live in a constant state of existential torment.”

Lewis Gordon, too, highlights in Bad Faith and Antiblack Racism the undecidability of black bodies as “literal containers of the power of state ideology.” Reading Spillers, Holland, and Gordon alongside each other gives suggestive insights about the gendered experiences of the black subject. Gordon draws attention to the fragility of black manhood, which inhabits a feminized position in relationship to legitimate heteropatriarchal White masculinity. He notes that “a black man in the presence of whiteness stands as a hole to be filled.” Gordon states that in an anti-black world “Blackness is regarded as a hole. Black men are hence penises that are holes; and black women are vaginas that are holes—holes that are holes. If blackness is a hole, and women are holes, what are white women, and what are black men in an antiblack world?”

Dialogue:

Man: Wat is daar de naam van eigenlijk als je een vrouwelijke Zwarte Piet bent? Het is gewoon unisex toch? [What’s actually the name of a female Zwarte Piet? It’s just unisex right?]

The black male body, which “embodies femininity even more than the white woman,” proves a complex site for White desire. “The ‘essence’ of blackness,” Gordon contends, “from the standpoint of the antiblack racist is, if you will, the hole, and the hole is the institutional bad-faith mode of the feminine. Antiblack racism is therefore connected to misogyny.”

The conflation of the female and the male in the figure of Zwarte Piet, by way of thingification, underscores Lewis Gordon’s argument and highlights another crucial point Hortense Spillers makes—she contends that “black is vestibular to culture,” that is “the black person mirrored for the society around her what a human being was not.” [her italics] The gendered black subject is an impossible subject.

Zwarte Piet is the not. As a representation of blackness, Zwarte Piet is a gender amalgamation, at once hypermasculine and vacillating between feminine and infantile, and, as such, “a vicarious, disfiguring, joyful, pleasure, passionately enabling as well as substitutively dead.” The threatening dimensions of black male sexuality are effectively neutralized by the feminization and infantilization of Zwarte Piet. The discourse of infantilization, which was central to the beliefs that legitimized slavery as an institution of benevolent paternalism (as embodied by Sinterklaas), shape Zwarte Piet. Even though Zwarte Piet is infantilized she/he remains by way of the fiction of black sexual excess the subject of erotic fascination. The White men in the porn video engage Zwarte Piet, the gender ambiguous black body, “a hole in being,” within the domains of sexual pleasure and desire, and this has profound implications for “race,” sexuality, and interracial sex.

In De Buitenvrouw (The Mistress), a book by Joost Zwagerman, which details the extramarital affair between Theo Altena, a White Autochtoon Dutch teacher, who teaches Dutch language, and Iris Pompier, a Black Surinamese teacher, who, not unimportantly, teaches physical education, Zwagerman writes about the main character Theo,

“Sometimes he would first push by way of ritual exploration with his dick against the thick dot of pubic hair—which fanned out to her groin; his foreskin softly chafing against the frizzy hair—before disappearing, always with an incomprehensible and almost frightening ease, in one seamless movement into her, straight into her amorphous warmth, his dick the concentrate of a congealed life, and her cunt everything but a refrigerator, instead a crematorium in full operation…”

In addition, Theo fantasizes,

“That we play act I’m dead and you desperately try to bring me back to life again. That you’re a black coffin made of living rock in which I will come to lie, I, the cold white corpse in a glowing sarcophagus.”

Zwagerman’s imageries do not deviate, at all, from the myths enveloping the black female body, which narrate black female sexuality as pathology. Black female sexuality is presented as amorphous, dangerous, primitive, sadistic, consuming, and death-threatening. Iris’ pussy isn’t simply hot (to reference bell hooks’ essay); it is scorching—ready to reduce, by fire, Theo’s “dead” body to ashes. The black female body does not only bring death, the black female body also acts as a receptacle of the dead—she is a “black coffin.” Iris is simply a black hole, that is a hole, to contain Theo’s withered White body.

To be white, in De Buitenvrouw, is to be an object of terror to oneself and blackness is the only thing that can neutralize the terror of Whiteness. Zwagerman plays with this perception throughout his book. Tom DiPiero posits that “the representation of both whiteness and masculinity [are] not so much identities as ‘hysterical responses to a perceived lack of identity’” and De Buitenvrouw, as well as Zwarte Piet, “‘endorse the position that white men are justified in asking others to determine their identity’.” The White male subject derives his dominance not from what he is but from what he isn’t. He relies on people of colour to show him what his powers really are. Sara Ahmed draws attention to this dynamic in Queer Phenomenology when she writes,

“In some fantasies of interracial intimacy, the white body becomes all the more white in its very orientation toward racial others as objects of desire. In her work, bell hooks (1992) examines how the white body’s desire for racial others is a technology for the reproduction of whiteness, which she describes as “eating the other.” If the white body “eats” such others, or takes them in, then it does not lose itself: the white body acquires color through such acts of incorporation; it gets reproduced by becoming other than itself. To become black through proximity to others is not to be black; it is to be “not black” by the very extension of the body toward blackness.”

There’s an entrenched belief in the Netherlands that anti-black racism is a thing of the past, or at least not a serious case of concern, due to an incorporation of black subjects. However, anti-black racism doesn’t merely linger on the surface skin of society, it is embedded in social policies, in our visual culture, and the various processes through which White people connect race, pleasure and service.

Much of anti-racism work in the Netherlands is made contingent on the “suffering body of colour.” Without any “complaints” there is no racism. We are invited to recount our stories of racial pain, to perform our hurting for the White gaze. If a suffering body of colour is necessary for an action to be recognized as racist then the difference between “being racist” and “being not–racist” is only made possible through the presence of a person of colour who bears bodily witness to racism (who feels its effects). This dynamic not only erases the fact that racism was constitutive of Dutch society, but it also fixes us in the subject position of victim and enables very limiting and disempowering ways of fighting against institutional racism.

In a recent article Asha ten Broeke writes that Black pain is worth less than White pleasure. However, as I’ve argued in this piece: Black pain is White pleasure, or rather Black pain serves as a passageway to White pleasure. There is a close relation between sexual pleasure and racial anxiety and Hazel Carby suggests that racialized anxiety leads “repeatedly to the debasement of the black and brown body in symbolic spectacle.” These scenes of subjection, from Zwarte Piet as a happy buffoon to Zwarte Piet porn, reinforce the idea of Black people being fundamentally “vehicles for white enjoyment.”

The issue at the heart of the Zwarte Piet debate is the brutal dilemma that Anthony Paul Farley poses when he writes, “What’s to be done when your subalternation, your pain, is the source of a pleasure which supports a political order which, in turn, ensures your subalternation?” What is, indeed, to be done when white pleasure is centred on black pain? That is the hard reality we all have to face.

[The title of this post I took from this poem, which deserves a post of its own.]

This is a really thought-provoking article. My husband said today that the movement to boycott/ban Zwarte Piet should focus, in a business-like way, on “it’s against the law: it’s insulting discriminiation- but omit the fact that it’s emotionally painful/upsetting. The latter puts ourselves in a position of pity- and is less effective. I think he has a point. The latter relies on empathy, whereas the former is already a universally accepted standard (that black face, especially in this context is demeaning.)

And yet our people grow up to become one of the most tolerant people in the world in a country where human rights, well-being and freedom of speech and religion are considered one of the best in the world. Children don’t associate this tradition with racism, only foreigners do. I could understand the confusion, but it’s a fact that it’s completely harmless. Especially because it’s well-known that his face is black from bringing presents through the chimney. Go make your own country a better place before pointing your finger at something you don’t understand.

…Children don’t associate that celebration with racism?

Unfortunatunaly children don’t remain child over time. That’s how you use a completely lunatic reasoning to justify something going on in your society. With November aproaching, the majority of Dutch fellows cannot think clearly. It’s as if something has blocked your capacity of reasoning objectively. Amazing!

Stupid I rather say. It’s you who don’t understand your own multicultural society. In a multicultural field one can’t make any point defending something that keeps hurting a subgroup with the same society. It’s called social exclusion, not a “samenleving”. Or don’t you understand your own vocabulary?

You bringing this topic to a geographic political entities level (countries) shows a very low education, which is also a national problem in the Netherlands. People have degrees but aren’t educated at all. If everybody has to think in term of country, African rather go back to their continent and begin cutting with producing of coffee and chocolate for instance. The world doesn’t function strictly in term of countries and mostly not to people who depend from exchange with abroad.

Most of you guy with nationalistic geographical argument are just ignorant.

Stupid uneducated asses!

“And yet our people grow up to become one of the most tolerant people in the world”

I had to laugh at that one. No, everyone who has been trained to think critically and has studied the Dutch has come to the same conclusion, namely, that the Dutch really aren’t as tolerant as they think they are. Let us use YOU as an example, shall we?

You said: “Go make your own country a better place before pointing your finger at something you don’t understand.”

See what you did there? Instead of carefully considering criticism with an open mind, you resort to a fallacious rhetorical tactic called the ‘ad hominem to quoque’. The fact that the culture of someone critical of yours is itself not perfect doesn’t mean that his criticism of your culture isn’t valid.

Moreover, you are also committing the psychologist’s fallacy by presupposing that your own point of view s objective, and assuming that, in the case of the writer, Sinterklaas is “something you don’t understand”.

Your further prove your own lack of objectivity by claiming: “Children don’t associate this tradition with racism, only foreigners do”

Only foreigners do? Sorry Siep, als Nederlander ben ik van mening dat Sinterklaas wel degelijk racistisch is. Je drogredenering “only foreigners do” is bij deze dus ontkracht.

Now, you’d probably reply by saying ‘Yes, Jay, but even though you’re also Dutch, most of us don’t think it’s racist. And that would be yet another form of fallacious reasoning (drogredenering) called the ‘argumentum ad populum. At some point most people thought the Earth was flat. Wasn’t true though, was it?

“I could understand the confusion but it’s a fact that it’s completely harmless.”

A FACT? I can understand your confusion, but it’s a fact that you’re a complete moron. See what I did there? Offended? Do you realize why your assertion of ‘fact’ was idiotic? I know several people (who grew up within the Dutch culture, and are therefore not foreigners) who were emotionally harmed by the Sinterklaas/Zwarte Piet dynamic. Dus je drogredenering “completely harmless” is bij deze ook ontkracht.

“Especially because it’s well-known that his face is black from bringing presents through the chimney.”

And the red lips and curls are because of …? And why aren’t the clothes stained or the presents dirtied? Besides, the face paint they use nowadays is brown.

See how ‘tolerant’ YOU are? I easily debunked all your fallacious arguments. Je hebt allerlei eenvouding te ontkrachten drogredenen gebruikt, maar geen enkele echte logisch houdbare argument. Leer kritisch nadenken man … vooral over je eigen cultuur!

The most tolerant people in the world? Which people would that be, certainly not the inhabitants of contemporary Netherlands.

It’s a mythe.

Empathy reduces with genetic distance.

Psychopaths are the ones that can be non racist.

The most tolerant people in the world are people with Williams syndrome.

Food for thought!

Thnx for all the attention to Zwarte Piet, it shifts attention away from rascism. I grow up with Piet Römer as Zwarte Piet. He always helped Sinterklaas when he made a mistake, because he was smarter than the white catholic bisshop. Zwarte Piet is doing all the jobs from poems to creatively wrapping up packets. The party is used in families to make fun of each other or showing respect for each other. Poems are ofter underlingned by Sint and Piet. Your right you can use every thjing in a racist way, from negerzoenen to blanke vla.

Reblogged this on thepietproject and commented:

wow!

Thank you for this thought-provoking analysis. It’s a subject I, as a white person growing up in a white dominated society (NL), am still wrapping my head around. It’s difficult to challenge my own thoughts on this, still living in that white dominated country. I enjoy reading pieces like this, as they expose what is normally not exposed. The more I pay attention, the more I get annoyed with how ‘we’ (the white majority of the NL) keep each other racist, intolerant and stupid by not even taking the Zwarte Piet discussion seriously, as is again illustrated by the likes of Siep and martin, above. The Netherlands is so convinced it’s tolerant, it will not tolerate discussion of it.

So, an old white guy using children / little people to work for him all year round, to make toys and serve him without getting paid, while the old white guy only works one day a year using a sled pulled by reindeers, is not offensive, degrading, rasist and animal cruelty? Just because you call him Santa Claus with his Elfs? The same Santa Claus, by the way, who is Coca-Cola’s version of Sint Nikolaas aka Sinterklaas.

Or thanking (God or someone) for taking a whole continent from the indigenous population (and killing them) by killing millions of turkeys is not degrading and rasist? Just because you call it Thanksgiving?

And celebrating the man that that discovered the “new world” and eradication it’s inhabitants, is not rasisit and offensive? Just because you call it Columbus Day and you have a day off?

I’m not saying that Sinterklaas and his Pieten is not offensive or hurtfull to some people, don’t get me wrong. But don’t forget, there are more strange celbrations in this world that are not offensive to some, yet are for others, but are still called tradition.

Reblogged this on Too Much Black.

Reblogged this on ronaldwederfoort.